Probation and Parole

By Bradley Keen , Senior Budget Analyst | 3 years ago

Public Safety Analyst: Bradley Keen, Senior Budget Analyst

Probation and parole are forms of supervision that allow defendants and convicted offenders to live in the community without compromising public safety. State parole agents and county probation officers monitor their progress through required rehabilitative programs and help to make sure that they remain crime free.

The average annual cost of community supervision is less than a tenth of the cost of incarceration, making it a valuable public safety tool for some cases.

The parole board decides who is released from state prisons and how they will be supervised in the community. It also sets guidelines for probation and parole supervision and audits supervision at the county level.

Parole Board

The Pennsylvania Board of Probation and Parole (PBPP) is an independent administrative board. Its nine members are appointed by the governor and confirmed by the Senate.

The board has the power to parole, or grant supervised release to, state prison inmates after they have served their minimum sentence. Before the board decides to grant or deny parole, staff prepare a parole file, investigate the circumstances of the offense, and facilitate victim input. If the board grants parole, PBPP works with the Department of Corrections to prepare the inmate to be released into parole supervision in the community. Each parolee must have an approved home plan and pre-parole drug testing. Some offenders are sent to community corrections centers to begin transitioning back to the community until they have an approved home plan.

If a parolee is re-committed for violating the conditions of their parole, the board is responsible for deciding if and when the person can be re-paroled, and whether the time spent on parole before the violation will count towards completion of his or her sentence. Re-commitment guidelines for parole violations are laid out in statute and range from a short stay in a parole violator center for minor technical violations, to return to a state prison for the duration of the maximum sentence (for more serious and/or repeated violations).

Budget Structure

Historically, the Board of Probation and Parole was primarily funded by three General Fund appropriations for general government operations, county grant-in-aid, and the Sexual Offenders Assessment Board. In 2017/18, the budgets for Corrections and Parole were consolidated to include a combined appropriation for general government operations, and distinct appropriations for state field supervision (parole agents and field offices), the parole board, and the Office of the Victim Advocate.

Act 114 of 2019 transferred county probation and parole oversight to the Pennsylvania Commission of Crime and Delinquency (PCCD). The two main state funding streams for county probation and parole are Intermediate Punishment Treatment Programs (County Intermediate Punishment) and Improvement of Adult Probation Services (county grant-in-aid). These programs were funded at $18.2 million and $16.2 million in 2021/22 respectively. The fiscal code stipulates that 80% of CIP funding must go to cover the cost of the actual treatment of offenders, and only 20% can be spent on county personnel. County grant-in-aid funding is only for personnel costs.

lt;span style="font-size:10pt">Act 59 (Senate Bill 411) of 2021 finalized the consolidation of the Department of Corrections and the Board of Probation and Parole. It is estimated that the final passage of this legislation will save the department $10.5 million through 2023/2024 due to increased capacity in the State Drug Treatment Program (STDP) and a decline in overtime for transportation-related duties.

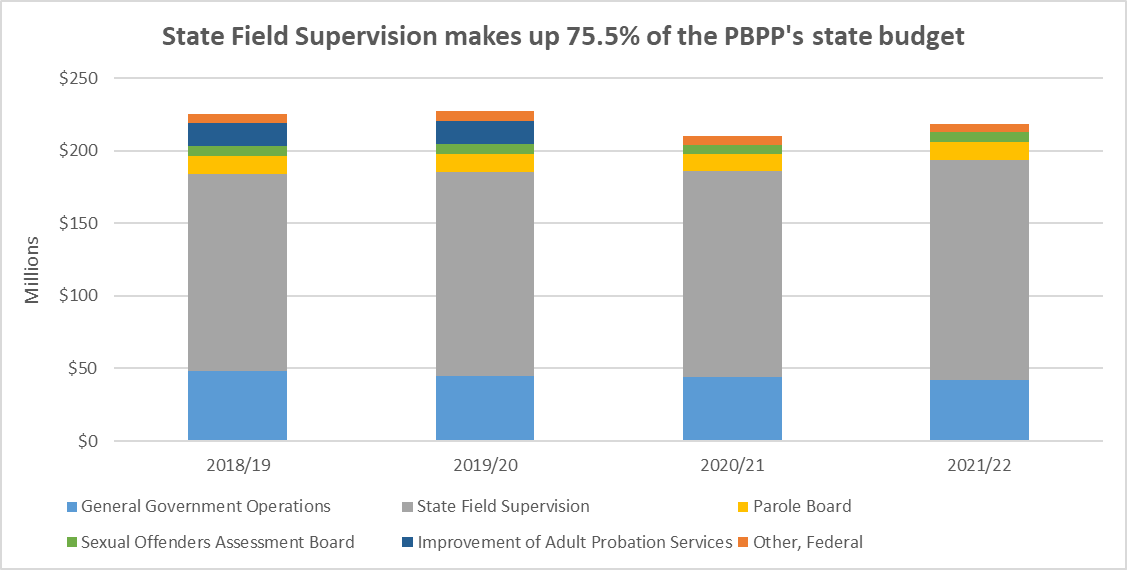

Under both budget structures, General Fund appropriations are augmented by monthly supervision fees paid by offenders on probation and parole. Supervision fees augment appropriations to pay for state and county supervision respectively, depending on where they were collected. State field supervision makes up 75.5 percent of the department’s state budget.

The next two sections look closer at state and county community supervision, the many forms they take, and the different funding approaches.

State Parole

When a sentenced inmate is released before their maximum sentence date, they still must serve the remainder of their sentence – but they do it in the community on parole.

State parole agents supervise cases originating from state and county sentences, as well as transfers from other states via the Interstate Compact for Adult Offender Supervision. The majority, 74 percent, are state sentences. County cases make up 18.5 percent of the state parole caseload, which includes probation supervision for counties that do not have probation offices (Mercer and Venango counties), and cases specially assigned by the courts. Transfers from other states make up approximately 8 percent of the caseload.

Parole vs. release without supervision

Parolees are required to follow a supervision plan customized to their risks and needs to help them reintegrate into the community. For example, a plan might require the offender to participate in substance abuse treatment and education, or it may require them to get a job, pay back restitution, or make other community contributions. Parole agents help offenders get into the services they need by working with community resources and contracted social service providers.

In contrast, inmates who serve their entire sentence in prison, known as maxing out, may be released back to the community with fewer resources and no supervision.

A 2013 recidivism analysis by the Department of Corrections found Pennsylvania inmates released on parole, compared to inmates who were released without community supervision after serving their maximum sentence, showed reduced recidivism rates within three years of being released. The re-arrest rate for parolees was 47.1 percent compared to 62.0 percent for their peers who did not receive community supervision, and the reincarceration rate for parolees was 19.4 percent (excluding technical violations), compared to the non-community supervision baseline of 20.4 percent.

Act 10 of 2018 mandated an additional 3-year probation sentence following release from prison for sex offenders, who are more likely to max-out in prison and would otherwise be released without community supervision. The court has authority under the new law to order the probation supervision to be provided by state parole agents or by county probation officers.

Personnel is the primary cost driver

Personnel expenditures made up approximately 89 percent of state field supervision spending in 2021/22. This is not surprising given the largely mobile workforce in the community. In 2016/17, the board worked to implement new work models and technology designed to make parole agents less reliant on physical office space and paper files. These changes corresponded with a decrease in operational and fixed asset expenditures for PBPP in 2016/17. At the same time, the board worked to keep the complement up to maintain a low caseload in line with national guidelines for effective supervision. The recommended standard caseload per agent is 50:1 for medium and high-risk offenders.

Despite hiring more agents and annual personnel expense increases, the cost of parole supervision is still cheaper than other supervision alternatives.

County Probation

County probation departments supervise a wide range of individuals, including those who are out of jail on bail while they await trial, participants in diversion programs, sentenced to probation or county intermediate punishment, or have been released from county jails on parole. Some county probation officers are assigned special caseloads in coordination with a treatment court, and some others supervise offenders on electronic monitoring or house arrest.

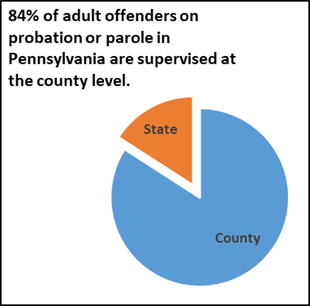

Across the commonwealth, 65 county probation departments supervise approximately 188,597 offenders in the community. Mercer and Venango counties do not have adult probation departments and are under the jurisdiction of state parole agents.

County probation offices are not under the jurisdiction of the Pennsylvania Board of Probation and Parole, but PBPP provides oversight, technical assistance, and grants. PBPP annually audits the probation departments to ensure compliance with the American Correctional Association standards for adult probation and parole. A county must maintain 90 percent compliance with the standards to be eligible to receive state grant-in-aid funding.

County Probation Funding

Counties rely on state funds for 30 percent of their annual budgets, but there are wide variations in how much they rely on different funding sources (LBFC analysis, 2015). State funding includes the grant-in-aid program and grants administered by PCCD. The other 70 percent of funding comes from county funds, supervision fees paid by offenders (a portion of which passes through the state treasury), and other sources that include various fees and grants.

In addition to the grants described below, PBPP also provides firearms training for county probation officers.

Grant-In-Aid: The grant-in-aid program, operated by the Board since 1966/67 and currently operated by PCCD (Act 114 of 2019), provides state funding for county probation departments. The funding pays for the costs of additional probation personnel necessary to carry out pre-sentence investigations (which, otherwise, courts may order PBPP to complete) and to improve the quality of probation services. The grant program is funded by a General Fund appropriation for the improvement of adult probation services and is distributed to counties based on the number of eligible personnel employed by each department in excess of the number employed in the base year (1966) up to a cap amount (1,014 positions statewide).

PCCD Grants: Counties also receive grants administered by PCCD. One category of PCCD grants that affects probation departments is an annual General Fund appropriation for county intermediate punishment programs, or CIP ($18.2 million per year). CIP grants awarded to counties often pay a portion of probation officer salaries.

Supervision Fees: County-supervised offenders are required to pay monthly fees to offset the cost of their supervision. In 2019, the average supervision fee for county offenders was $44 per month. Prior to the passage of Act 77 of 2022 (HB 2464), state law required the county to retain half of the amount collected to pay for probation services and remit the balance to a state treasury-maintained restricted receipt account for county probation supervision fees (the Crime Victims Act of 1998, Chapter 11 relating to financial matters). Money in the restricted account was then returned to counties as an augmentation to the appropriation for grant-in-aid funding. Historically, the commonwealth has returned these fees to the originating counties on a dollar-for-dollar basis. Act 77 of 2022 simplified this process by removing the requirement to remit the balance to the state restricted receipt account; 100% of the fees are now retained by the county.

Consolidation of Corrections and Parole

The Pennsylvania Board of Probation and Parole and the Department of Corrections entered into a substantial memorandum of understanding (MOU) on Oct. 19, 2017, which recognized the overlapping functions and shared public safety objectives of the Board of Probation and Parole and the Department of Corrections. Under the MOU, the two agencies operated under a unified organizational structure.

Act 59 (Senate Bill 411) of 2021 finalized the consolidation of the Department of Corrections and the Board of Probation and Parole. It is estimated that the final passage of this legislation will save the department $10.5 million through 2023/2024 due to increased capacity in the State Drug Treatment Program (STDP) and a decline in overtime for transportation-related duties.

The Sexual Offenders Assessment Board

The Sexual Offenders Assessment Board conducts assessments of certain convicted sex offenders, including juveniles convicted of sexually violent acts. In 2021/22, the board was funded by a $6.6 million appropriation from the General Fund.

The Office of the Victim Advocate

The Office of the Victim Advocate collaborates with PBPP, the Department of Corrections, and PCCD to provide services for victims of crime. Principal among these, are notification services, address confidentiality, and assisting victims in exercising their rights to participate in the parole process.

Through 2016/17, the Office of the Victim Advocate was funded by a portion of the appropriation to PBPP for general government operations, a portion of the Department of Corrections’ appropriation for general government operations, and by federal funds. In 2017/18 and 2018/19 there was a dedicated appropriation for OVA from the General Fund of about $2.5 million per year. Since 2019/20 the program has received funding from within general government operations.

Terms and Definitions

Augmentation

Fees or institutional billings collected by the commonwealth and used to supplement a specific appropriation. Augmentations can usually be spent for the purposes authorized for the appropriation they augment without an additional appropriation in the General Appropriation Act.

County Intermediate Punishment

A sentence that is less restrictive than incarceration, but more restrictive than probation and incorporates specific programming requirements to address the cause of criminal behavior and reduce the risk of recidivism. Treatment courts are one form of intermediate punishment.

Probation

A sentence of community supervision ordered by the court. An individual may be sentenced to probation in lieu of incarceration, or for a period following incarceration.

Parole

Release from a correctional institution before the expiration of the maximum sentence, and the period of supervision in the community following a parole release.